Earlier this month, we announced that we would, twice a month, track how well our nation’s transportation and logistics supply chain is handling the increase in demand for goods as we recover from the pandemic. With the data for the full month of October now in, we continue to see the goods movement supply chain moving more goods than ever before, goods reaching stores, and the velocity of goods leaving the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach increasing.

Tracking progress at our ports

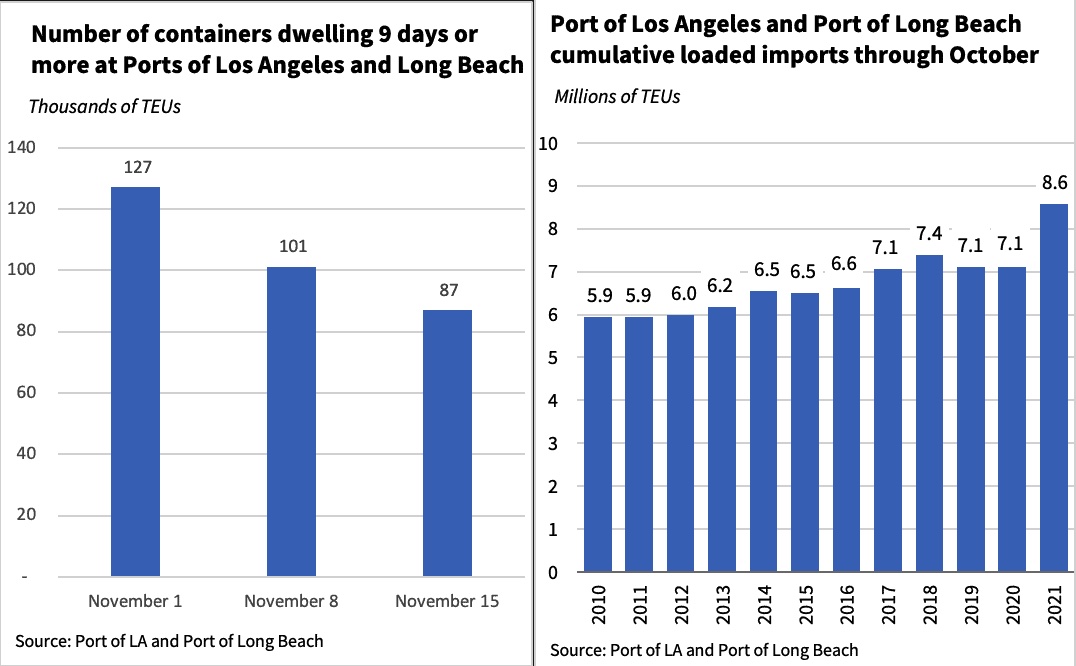

Yesterday, the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach offered preliminary estimates of 849,000 loaded containers imported in October. This brings the total number of containers they have imported between January and October to 8.6 million, which is 16 percent more than their previous record over the same period in 2018. The ports also reduced the number of containers sitting on the docks for more than 9 days by about one-third over the first two weeks of November.

We continue to monitor the ability of the goods movement supply chain to get goods from the ports to store shelves. Census data, specifically inflation-adjusted retail inventories without autos, show that the value of the goods on retailers’ store shelves and in their warehouses grew between the end of September and the end of October and is now 1 percent above its pre-pandemic level. Higher frequency data from IRI show that the share of consumer-packaged goods that are in stock was 90% last week, just one percentage point below its pre-pandemic level.

The goods movement chain is controlled by the private sector, which is why we have continued to work closely with the private sector to drive improvements to the system. Corporate leaders have recently reaffirmed that the system is successfully moving products. In discussing the holiday season, FedEx CEO Fred Smith said “I think we’re ready for this. This year we’re forecasting we will deliver 100 million more shipments in this holiday season than we did in 2019.” In a call with President Biden last week, Target CEO Brian Cornell “shared that we are ready to deliver a great shopping experience for guests this holiday season,” that inventories are higher than last year, and that they are seeing containers move at night at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Walmart said it had more products flowing through its supply chain than during the same period last year when pandemic demand for some products strained supply. Its U.S. inventory rose 11.5% in the quarter.

Reducing Congestion to Increase Velocity

The reduction in long-dwelling containers was due, in part, to a new congestion fee the ports imposed on ocean carriers. The carriers have been so successful at clearing the docks that the ports announced this week they would postpone charging the fee. Reducing the number of containers sitting at the port improves overall efficiency by creating more space for containers to be unloaded more quickly and giving trucks more room to maneuver.

However, the docks are not just full of loaded containers. Thousands of empty containers remain on the docks as well, often sitting on chassis. Without these chassis, trucks are unable to remove containers from the docks, and a shortage of chassis has contributed to the increase in dwell times at the ports. The ocean carriers have now agreed to clear more of these empties from the docks faster, including bringing in vessels dedicated to empty removal. Based on these new commitments, they have already cleared out 60,000 containers (measured in TEUs), with commitments to remove another 28,000.

Restoring Balance at our Ports

Our ports are not just important to bring goods into our country, but they also help U.S. businesses reach global markets, supporting millions of small businesses and jobs in communities nationwide. This is especially true for America’s farmers and the rural communities and businesses that rely on them. This year, agricultural exports from ports are up six percent compared to the same period last year, when measured by weight.

The strength in agricultural exports has been driven by non-containerized exports, which include items such as corn and rice and are up eight percent. However, approximately one quarter of agricultural exports by ship—which includes goods like cotton and fresh fruit— move by container and those volumes are down 2 percent this year. Our work to reduce congestion at the Port of Savannah—the top containerized agricultural export port in the country by number of containers—should help improve the flow of agricultural exports. With five pop-up container yards located throughout the Southeast, farmers will have more ways to get commodities via truck or rail to this critical port.

More work is still needed, however, to improve exports out of the nation’s ports. The rise in cost of shipping between Asia and the West Coast has meant that it is more profitable for the ocean carriers to quickly load empty containers or return without a full ship instead of waiting for loaded containers to get into the port. The share of exported containers at the two ports that are empty has risen from around 55 percent in the five years preceding the pandemic to over 70 percent so far this year.

This problem is affecting more businesses than just farms and raises questions about the fair treatment of American exporters and importers in the shipping industry. Today a system of global alliances dominates global shipping where nine carriers that have been organized into three alliances control about 80 percent of the global shipping market and 95 percent on the critical East-West trade lanes. Alliances only controlled 29 percent of the market as recently as 2011. This lack of competition leaves American businesses at the mercy of just three alliances. Retailers are charged fees for their container remaining on the docks, even if there is no way to move their containers. If the alliances decide to not accept exports, agricultural exporters will not be able to fulfill their contracts, and farmers’ perishable products may be left to rot.

In July, the President called attention to these problems in his Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, which encouraged the Federal Maritime Commission to vigorously enforce the prohibition against ocean carriers charging unfair fees to exporters and importers. The Federal Maritime Commission, which has jurisdiction to regulate the carriers, should use all of the tools at its disposal to ensure free and fair competition. It has already launched an inquiry into excessive shipping fees that are charged when the importer or exporter cannot plausibly move the container.

The FMC should consider using its other tools, too. For example, while the alliances between the carriers receive statutory immunity from antitrust laws, the FMC can challenge those agreements if they “produce an unreasonable reduction in transportation service or an unreasonable increase in transportation cost or … substantially lessen competition.” The Justice Department stands ready to lend the FMC its expertise and support. In fact, the two agencies have already increased their collaboration, which is part of the “whole of government” approach to promoting competition launched by the Executive Order on Competition.

Congress should take action here as well. The FMC needs more resources to oversee an industry with the size and scope of global shipping. Its annual budget is just around $30 million. Current laws also do not require even basic transparency in this sector. For example, there is no public reporting of the detention and demurrage fees carriers are charging their customers. Moreover, Congress should provide the FMC an updated toolbox to protect exporters, importers, and consumers from unfair practices. There is bipartisan support for doing this, including a bipartisan bill sponsored by California Democrat John Garamendi and South Dakota Republican Dusty Johnson. Their proposed legislation includes good first steps towards the type of longer-term reform to shipping laws that would strengthen America’s global competitiveness.

We look forward to working with members of both parties in Congress to ensure that we have a system of maritime regulation that boosts instead of reduces American competitiveness for both importers and exporters. That would complement the bipartisan infrastructure deal that the President signed into law this week, which is one step in the President’s broader strategy to build a more durable industrial strategy that will bolster America’s global economic competitiveness. Reforms to our shipping laws would help further improve our ability to get goods in and out of this country more quickly and cost effectively, and strengthen opportunities for U.S. businesses to connect with global markets.