John D. Porcari, Sameera Fazili, and Liz Reynolds

“Supply chains,” a term once reserved for business logistics teams, has now become a household phrase. Whether you’re shopping for a car, a refrigerator, or a sweater, delays and backlogs have drawn attention to the largely private sector systems responsible for both making goods and moving them from factories to shelves and doorsteps. These private systems are also global, and therefore the global nature of the pandemic has proven to be a profound disruption to supply chains since the pandemic first took hold in early 2020. That is why President Biden called for greater coordination between our closest trading partners to overcome these collective issues during the G-20 summit this weekend.

While supply chain disruptions remain a challenging side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, they now also signal the swift return of strong consumer demand in the U.S. after one of the deepest recessions on record. In this blog post, we detail how the Biden-Harris Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force is measuring and tracking the status of the leading drivers of disruptions in our transportation and logistics supply chain, and the steps we are taking to ensure that goods continue to reach the households and businesses who depend on them.

Rising Tides

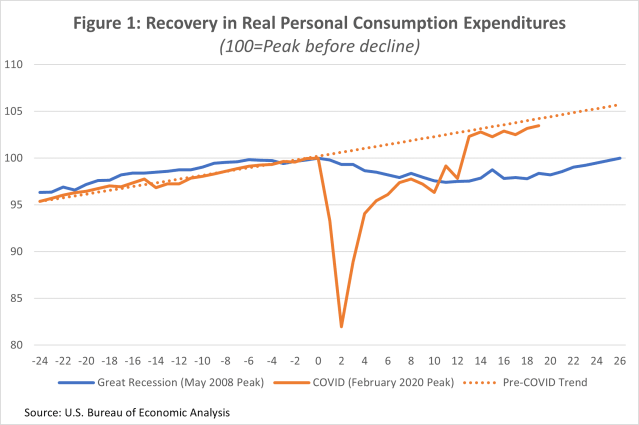

Since President Biden took office, nearly 5 million jobs have been created, the unemployment rate has dropped to below 5 percent, the number of people collecting unemployment insurance benefits has fallen by 2.5 million, and food insecurity has declined nearly 40 percent. President Biden’s economic agenda has propelled the United States to the fastest economic growth in nearly 40 years over the first three quarters of this year, and over the pandemic as a whole the U.S. leads G7 countries in its recovery. As a result of this historically strong recovery, American families have been able to return their overall spending to pre-pandemic trends. This marks a stark contrast with this point in previous economic recoveries.

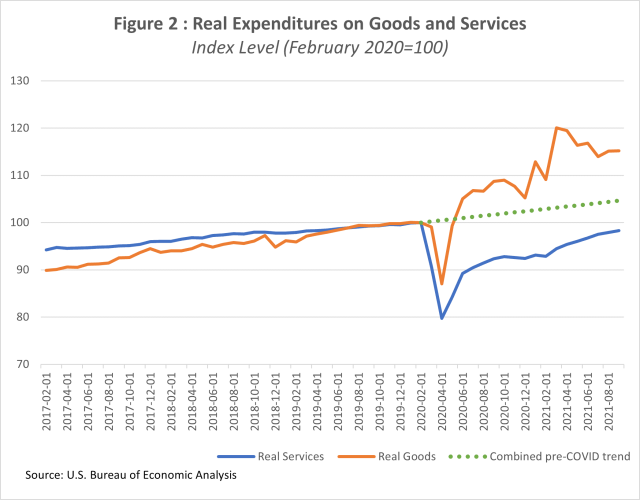

But while overall consumer spending is almost back to its pre-pandemic trend, the composition of that spending is quite different. Since the pandemic, consumer purchases of goods—like furniture, appliances, and food—has shot past pre-pandemic levels, and spending on services—like healthcare and vacations—has not yet returned to pre-pandemic trend levels. As the pandemic recedes, spending on goods is expected to decline and spending on services to rise. We are already seeing that with spending on goods in September well below its April 2021 peak, but we still have a ways to go. In the meantime, our supply chains are moving record volumes of goods – and being asked to continue to do so. They also must withstand ongoing disruptions due to the global pandemic, as shipping delays due to the delta variant has demonstrated. The reshuffling of spending from services to goods as the public health situation improves will be critical for reducing disruptions.

Our Periscope on Supply Chains

Starting today, we will be publishing a twice monthly dashboard of metrics to track progress at both the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, and in the economy at large. Here, we explain what we are tracking and why it matters.

Ships at Anchor

One of the most visible and widely reported-on indicators that the demand for goods remains abnormally high is the number of container ships waiting to dock at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which together handle 40 percent of containerized imports entering the country. Normally, there are only few container ships “at anchor” waiting to dock; on Friday, there were 75. This number is partly driven by consumer demand for goods, and also impacted by delta-related port and factory shutdowns in Asia.

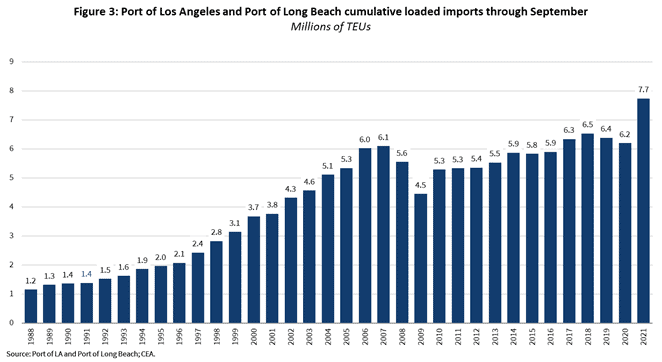

Cumulative Import Volume

A closer look shows that in fact more—not less—goods are moving through our transportation and logistics supply chain, across our ports, warehouses, and stores. This can be seen by looking at the volume of containers (as measured by twenty-foot equivalent units or TEUs) coming into the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach (Figure 3). Between January and September, over 7 million loaded containers were imported, 18 percent higher than over the same period in 2018, which had been the previous record.

The Biden-Harris Administration will be closely tracking the cumulative number of imported containers processed for the rest of the year and will be highlighting data twice a month. Preliminary data for the first half of October indicates that the ports imported nearly 380,0000 loaded containers for a cumulative 8.1 million containers imported this year. That suggests the ports remain significantly ahead of where they were at the same point in 2018 and are on pace to break new records by year’s end.

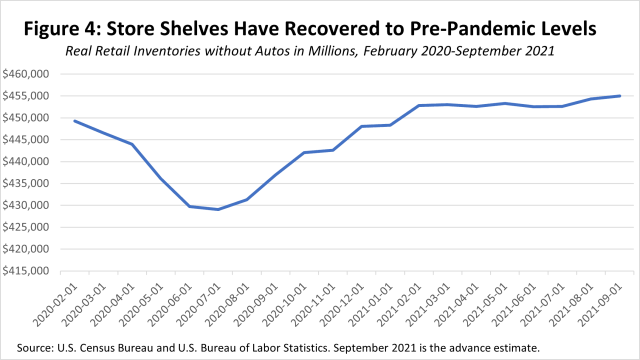

Retail Inventories

It’s not enough to move goods into the country—we also need to make sure that we get them on shelves. The gold-standard U.S. Census Bureau data suggests that the rest of the supply chain is in fact succeeding in keeping store shelves stocked. Inflation-adjusted retail inventories excluding autos grew between the end of August and the end of September. And at the end of September, they were 4 percent higher than they were a year ago and are actually above pre-pandemic levels (Figure 4). We have excluded autos from this measure because the decline in auto inventories is a result of a global semiconductor shortage affecting the autos sector worldwide, including in large auto producing countries like Germany and Japan.

Other real time measures of availability of goods in stores—such as the IRI Supply Index—similarly shows that retail stores’ rates of keeping goods in-stock is 89 percent, near the pre-COVID level of 91 percent. These higher frequency data measures also suggest that, as recently as last week, there had been no deterioration in retail inventories since the Census reported the end of September retail inventory numbers.

We will continue to track cumulative container imports, retail inventory levels, and in-stock indicators, to help us monitor the ability of this historically high volume of goods to make their way to warehouses and store shelves, comparing inventory levels to the pre-pandemic period. Throughout this work, we will remain focused on increasing velocity and fluidity along the goods movement supply chain, working in close partnership with the private sector. Our commitment to tackle bottlenecks and inefficiencies is aimed at helping to get goods to the families and businesses that need them as our economy continues to recover from the pandemic. We will also continue to closely watch the rotation from goods to services consumption, as we expect that rotation to ease pressures on the goods movement supply chain.

Lifting more Boats

As U.S. consumers continue to purchase goods at a high level, decades of neglect and underinvestment in our infrastructure have left the links in our goods movement supply chains struggling to keep up with the rapid and persistent increase in goods movement that the pandemic has generated.

This poses a collective action problem in the largely private system that moves containers of goods from ships to docks to trains and trucks to get distributed to warehouses, factories, and stores. Which is why the President issued a call to action to encourage every link in the goods movement chain to move towards a 24/7 pace to increase the volume and pace of products flowing through the system. The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) workers joined together to make the first commitment. Some of the countries’ largest companies joined in as well—including Walmart, Target, FedEx, UPS, Home Depot, and Samsung—committing to try a new solution.

Since then, others have also joined in. The state of California stepped up, issuing an executive order to identify state-owned sites to serve as temporary warehouses and allow trucks to carry more goods. The City of Long Beach next helped create more storage space through a temporary zoning change to facilitate container storage. Just in the last week, Union Pacific, one of the two major railroads responsible for moving goods out of the port, announced it would operate its station near the ports 24/7 and offer discounts to customers for each container they moved by rail. In addition, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) and the State of California announced a $5 billion partnership to modernize California’s goods movement chain, strengthening the capacity and resiliency of the nation’s key import and export hub. The result of these combined efforts will be more space available to store containers and faster paths for containers to exit and enter the ports.

These “pull” strategies are important first steps, and we will continue to do more to energize the private companies that drive the goods movement chain. This includes supporting the ports’ decision to fine containers that stay on the docks too long. The system of loading boxes off ships, onto docks, onto trains or trucks, and out of the port’s gates relies on collaboration between private companies including ocean carriers, terminal operators, cargo owners, freight forwarders and trucking companies. With more rail cars now operating, there is more capacity to move goods out of the ports. And some of the largest retailers have committed to move more goods at off-peak hours. The system is primed to move a historic volume of goods, with the companies that drive the goods movement chain coming together to take action.

Moving Forward

This is precisely what the Biden-Harris Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force has been set up to do: act as an honest broker to encourage companies, workers, and others to stop finger-pointing and start collaborating. Many have responded to this call, recognizing that a once-in-a-century pandemic requires us all to do our part to support our nation’s economic recovery. Moving all links in the supply chain simultaneously doesn’t happen overnight, but the actions being taken by every link in the chain are making a difference. These actions are starting to clear the backlogs and break down the barriers that have made it hard to move this unprecedented volume of goods.

We will also continue to track how well our nation’s transportation and logistics supply chain is handling this increased flow. We will report cumulative imports through Los Angeles and Long Beach, retail inventories, and the number of ships at anchor at the two ports on a twice-a-month basis through at least the end of the year.

We need to seize this moment to strengthen our country’s future competitiveness by focusing longer term on building the resilience of our nation’s supply chains. That includes a goods movement chain that is more resilient, fluid, and can operate at a higher velocity. For too long, our country has underinvested in the roads, railways, ports and projects that propel goods movement. With the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, we can make the fundamental changes that are long overdue for our ports, rail and roads. This is how we build back better, with government bringing workers and businesses together to leverage American ingenuity to tackle the challenges brought on by a global pandemic.